In April 1933, Hitler shocked world opinion with a nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses and the removal of all Jews from the civil service and the professions. However, the Nazi attack on the Jews did not come out of the blue. Anti-Jewish propaganda, discrimination and violence were an integral feature of everyday life during the Weimar Republic.

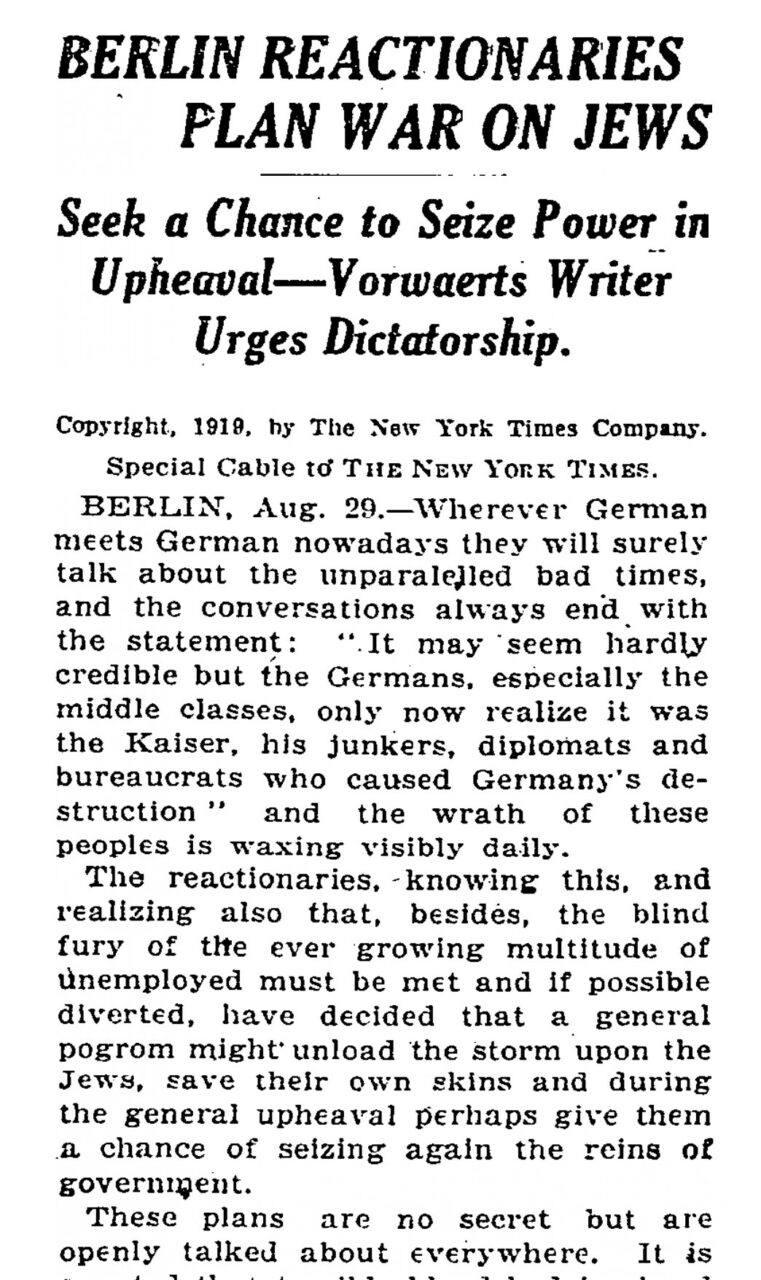

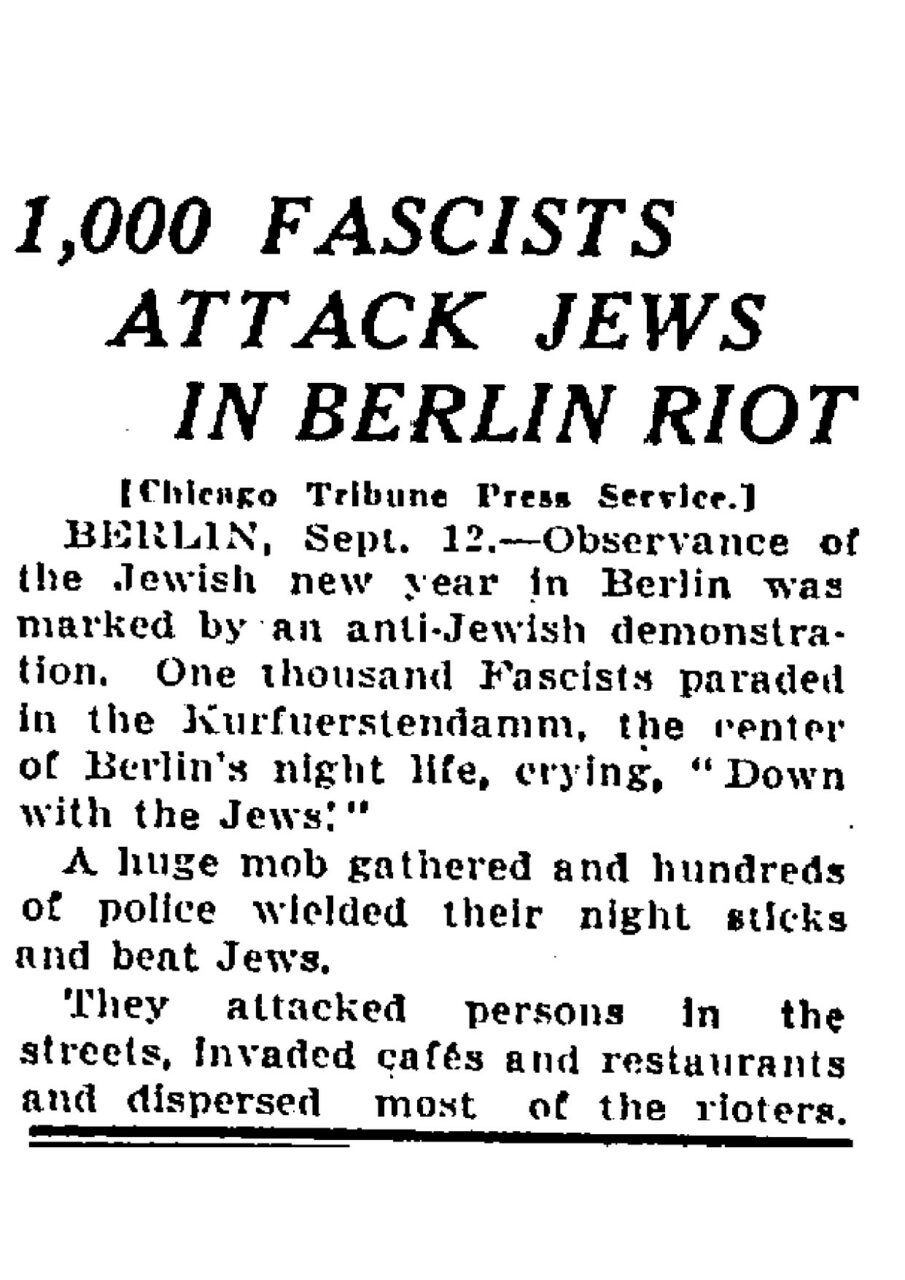

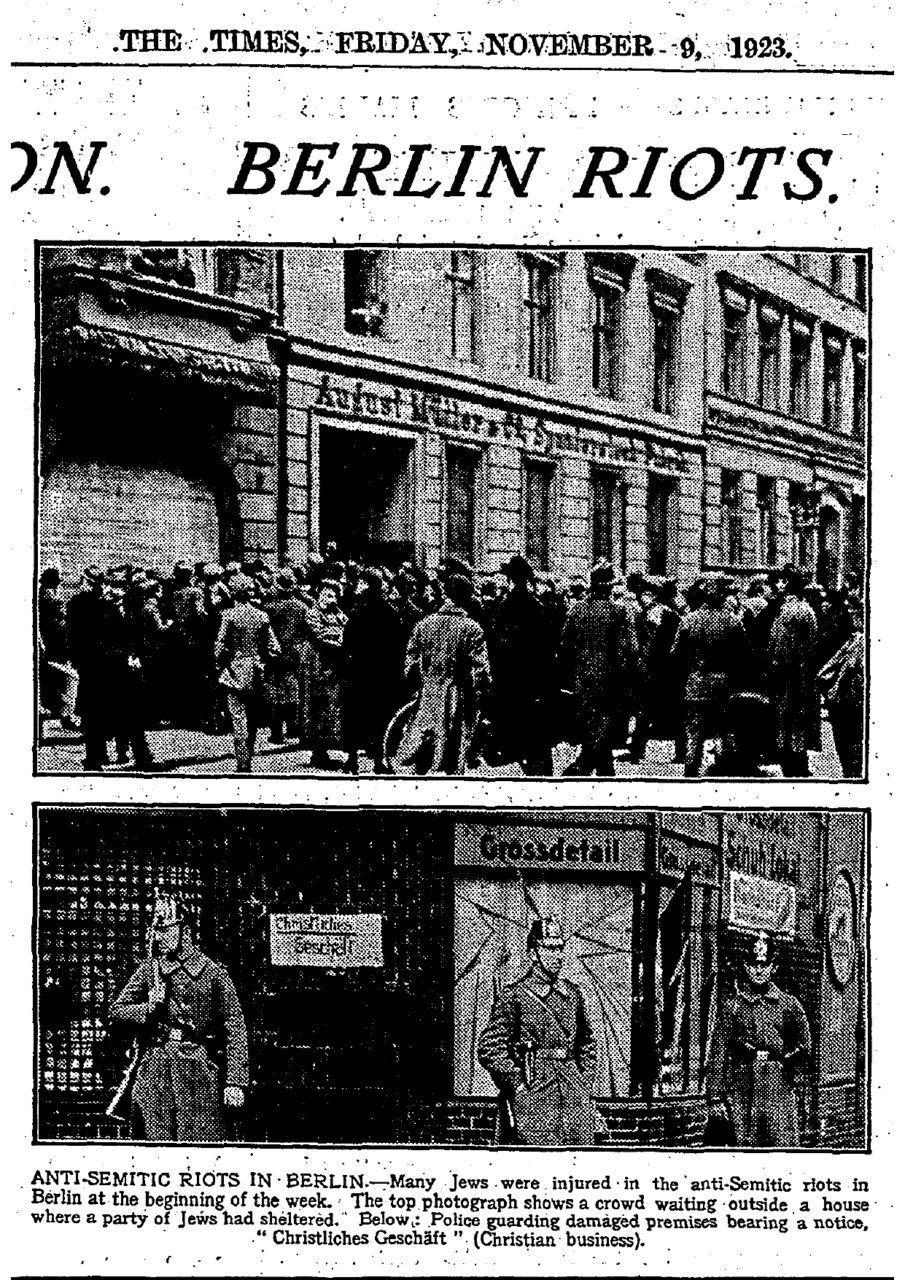

After the First World War, a wave of antisemitism swept through Germany. Reactionary and völkisch groups accused the Jews of being responsible for the military defeat, for Germany’s economic hardships and for the revolution that brushed aside the monarchy. Given the prominent role played by Jews in the revolution and foundation of the Weimar Republic, the reactionaries fanatically defamed the latter as a “Jewish republic”. During 1919-1922 numerous Jewish politicians were murdered, among them Rosa Luxemburg, Kurt Eisner and Walther Rathenau.

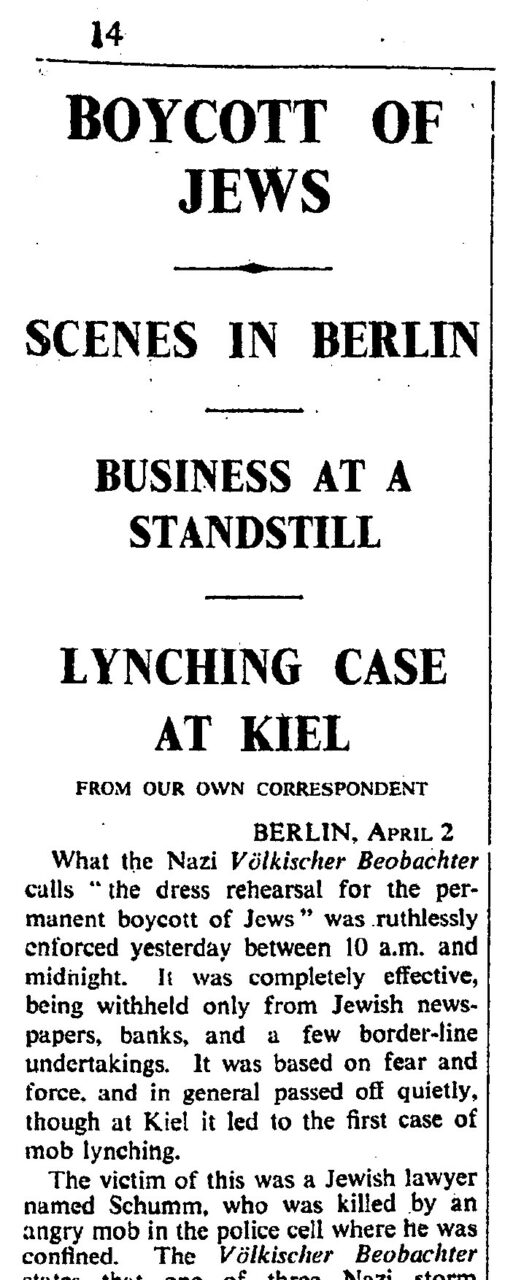

After a calmer period from 1924 to 1929, antisemitic propaganda and violence increased again with the rise of the Nazis between 1930-1933. Following Hitler’s seizure of power on 30 January 1933, anti-Jewish excesses exploded, culminating in the nation-wide boycott of Jewish businesses on 1 April and in the removal of the Jews from the professions shortly afterwards. The boycott provoked an outcry of indignation in the foreign press and led to mass demonstrations organised in protest against the National Socialists’ treatment of the Jews. To the international public, Hitler’s persecution of the Jews did not come without forewarning. Throughout the Weimar Republic, foreign newspapers reported repeatedly on antisemitic occurrences in Germany.

The project aims to contextualize and compare the responses of a number of leading newspapers in a selection of European and non-European countries. It focuses on key antisemitic incidents in Weimar Germany, ranging from anti-Jewish demonstrations in the wake of the First World War to the first months of Hitler’s dictatorship. The research shows how foreign journalists understood and explained to their readers the character and evolution of German antisemitism between 1918-1933, which was the breeding ground for later Nazi antisemitism. Moreover, the project not only shows how and why reactions varied in different countries and among different publications. It also shows what effects the press reports had on governments and societies in the countries under consideration. This approach has been tested in several pilot studies examining the reactions of British, American, French, Italian, and Austrian newspapers between 1918 and 1933.

The pilot studies reveal the European, indeed global, dimension of Weimar antisemitism. Anti-Jewish incidents were no longer of national, i.e. of German public interest alone, but triggered press responses and public debates on German-Jewish life beyond Germany’s borders. Through its manifold European and international dimensions, the press coverage of German antisemitism may be conceived of as a transnational media theme – a series of events and developments provoking intense responses, interactions, and entanglements and involving various media outlets, often with repercussions on political systems and societies across national borders.

Over the course of this research, two patterns of transnational interaction have emerged. First, there was a considerable degree of flow and exchange of information between German and foreign newspapers on the one hand, and on the other, among foreign papers themselves. This often led to direct quotations and the transfer of information. However, since foreign correspondents often based their own reports on German press articles, they also frequently transmitted ready-made interpretations of German antisemitism or anti-Jewish stereotypes. As a result, the German press shaped indirectly, but to a considerable degree, the perception of German antisemitism abroad.

A second transnational pattern was the interaction between the press, and societal and political actors in other countries. The repeated calls issued by American Rabbis and Jewish organizations between 1930-1932 for solidarity with German Jews in the face of Nazism constitute a case in point. The expulsion of eastern European Jews from Bavaria in the autumn of 1923 demonstrates that critical foreign press reports on German antisemitism did have political repercussions. In reaction to this criticism, officials of the German foreign office, deputies of the Reichstag, and representatives of the foreign press urged the reactionary Bavarian government to end its anti-Jewish policy because of its negative impact abroad.

This project has received funding from the University of Bremen’s institutional strategy ‘Ambitious and Agile’ under the Excellence Initiative launched by the German Federal Government and the German Federal States (EUR 9.990,00, in 2014), and from the University of Bremen’s Central Research Development Fund (EUR 2.500,00, in 2010).

You can find more information and research materials on the project website German Anti-Semitism and the Press during the Weimar Republic, 1918-1933.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1987-0413-508 / P. Buch / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Publications

Seul, Stephanie: “German Antisemitism and the International Press during the Weimar Republic, 1918-1933,” European Holocaust Studies 1 (2019), pp. 221-31.

Seul, Stephanie: “Transnational Press Discourses on German Antisemitism during the Weimar Republic: The Riots in Berlin’s Scheunenviertel, 1923,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 59 (2014), pp. 91-120.

Seul, Stephanie: “’Herr Hitler’s Nazis Hear an Echo of World Opinion’: British and American press responses to Nazi anti-Semitism, September 1930 – April 1933,” Politics, Religion & Ideology 14,3 (2013), pp. 412-30.

Seul, Stephanie: “’A mad spirit of revived and furious anti-Semitism’: Wahrnehmung und Deutung des deutschen Antisemitismus in der New York Times und in der Londoner Times, 1918-1923” [Perceptions of German Anti-Semitism in the New York Times and the London Times, 1918-1923], in Michael Nagel and Moshe Zimmermann (eds.), Judenfeindschaft und Antisemitismus in der deutschen Presse über fünf Jahrhunderte. Erscheinungsformen, Rezeption, Debatte und Gegenwehr. Bremen: edition lumière, 2013, vol. 2, pp. 499-525; PDF

Seul, Stephanie: “The British Press Coverage of German Anti-Semitism in the early Weimar Republic, 1918-1923,”, in Geraldine Horan, Felicity Rash and Daniel Wildmann (eds.), English and German Nationalist and Anti-Semitic Discourse, 1871-1945. Frankfurt/M., New York u.a.: Peter Lang, 2013, pp. 183-209.

Seul, Stephanie: “’A Menace to Jews Seen If Hitler Wins’: British and American Press Comment on German Anti-Semitism 1918-1933,” Jewish Historical Studies 44 (2012), pp. 75-102.