By Stephanie Seul

March is Women’s History Month, a celebration of the contributions women have made to history in a variety of fields. During the First World War, women from different nations covered the war on the major fronts and on the home front. They took personal risks and broke with social conventions of their times. To celebrate these courageous women, during March 2023 I posted on Twitter about one journalist each day. Here are my collected posts that highlight the contribution of women to the documentation of the conflict. Women war reporters from Europe, North America and Australia published their eyewitness accounts and photographs in newspapers, magazines and books. Newspapers around the world reprinted their accounts.

Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Comœdia, 9 March 1910

Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale der France

Denver Post (Denver, Colorado), 26 December 1914

Wikipedia

Andrée Viollis (1870-1950) was a French writer, journalist and feminist activist. During 1914-1916 she worked as a nurse in France. Moreover, she was a special correspondent for Le Petit Parisien (French paper with the biggest circulation) in France and England. She visited the British army bases along the Northern front and the Somme, observing especially the role of women. Her reports appeared also in the Revue de Paris and in Lectures pour tous. In 1919 she covered the Paris peace conference for the London Daily Mail, among others. She also served as editorial assistant to the London Times and the Daily Mail.

Colette (1873-1954, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette) was a well-known French writer (nominated for the Nobel prize in literature in 1948), journalist and actress. During the war she travelled to Verdun to meet her husband who was fighting at the front. She reported about the devastation brought about by the war and its effect on children and women in her weekly column ‘Le journal de Colette’ for Le Matin (the second-biggest newspaper in France). In 1917 she published her collected articles in the book Les Heures longues and received favourable reviews.

Mary Frances Billington (1862-1925) was an English writer and journalist. She was one of the founders and the president of the Society for Women Journalists during 1913-1920. In 1897 she was recruited to run the women’s department of the Daily Telegraph. She worked on the paper until her death. During the First World War Billington travelled to the front in France by arrangement with the British War Office. She visited the camps of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps and several military hospitals. Billington reported about the women’s work in the theatre of war and highlighted the bad management in some of the army camps. She published two collections of her war articles: The Red Cross in War (1914) and The Roll Call of Serving Women (1915). Throughout the war, Billington also regularly published articles in The Girl’s Own Paper and Woman’s Magazine.

Annie Christitch (1885-1977) was a Serbian-Irish journalist and Catholic suffragist. During the war she acted as a correspondent for the popular London Daily Express and as a nurse and relief worker in Serbia. She published more than 30 reports in the Daily Express. Several articles also appeared in other British and American papers. Her eye-witness accounts helped spread knowledge about the appalling war conditions in Serbia. Her war stories were reprinted in newspapers in the USA and the British Empire. Moreover, Christitch gave a series of lectures in Britain to raise money and equipment for Serbian hospitals. In late 1915 the Austro-Hungarian occupying forces detained Christitch, but she was able to continue her relief work. She returned to England in 1918 and resumed her career as a journalist and Catholic women’s activist.

Noëlle Roger (1874-1953) was a Swiss novelist, playwright, travel writer and journalist widely known in francophone Switzerland and France. A trained nurse prior to her literary career, during the war she worked in a French hospital near Lyon. In 1915 she published a series of articles in the Journal de Genève and the renowned periodical Semaine littéraire under the title Les Carnets d’une Infirmière. They were gathered and published as a highly acclaimed book in the same year. The reports evoke the noble suffering of the soldiers and praise the nurses’ skill and empathy in easing their suffering. Roger published several other war writings that bear witness to her continued humanitarian engagement in Switzerland and her empathy towards the civilian victims of the war. After visiting the devastated combat zones of Verdun in 1917, Roger published several journal articles. They were re-published in 1919 under the title Terres Dévastées et Cités Mortes.

Wikipedia

Sofía Casanova (1861-1958) was a Galician-Spanish expatriate novelist, poet, playwright, travel writer, journalist and social campaigner. Despite living in Poland after her marriage to a Polish philosopher, she published regularly in Spain. In 1915 she was invited by the Madrid daily ABC to become the paper’s Eastern European correspondent, a position she held until 1936. ABC was at that time the most widely read daily in neutral Spain. The paper had a conservative and pro-German stance, and Casanova was one of its star columnists. During the war, Casanova posted her articles from all over Poland and Russia, after her family’s evacuation during the invasion of Warsaw. In 1917 she witnessed the Russian Revolution in St. Petersburg. Casanova published more than 220 articles in ABC that chronicled the war on the Eastern Front. As a committed pacifist, she sharply criticised the destruction and injustice resulting from war. Casanova gathered her wartime columns in three books published 1916, 1917 and 1920.

Kitty Wentzel (1868-1961, Christiane Marie Baetzmann) was a Norwegian writer, journalist, sculptor, actress, translator and cultural historian. She worked as a journalist for Verdens Gang in 1913-17 and then for Ørebladet until 1924. In 1915, Wentzel went to St. Petersburg as a correspondent of the weekly magazine Urd. She portrayed life in the war-stricken city for the journal and witnessed the anti-German pogroms in Moscow in May 1915. Her eye-witness accounts of the looting and destruction of German shops and factories appeared in various Norwegian publications. Austrian and Hungarian newspapers reprinted her reports in July 1915.

Flavia Steno (1877-1946, Amelia Cottini Osta) was an Italian novelist and journalist. During the war she was one of few Italian female journalists admitted to the frontline on Mount Krn (Monte Nero) as official war correspondent for the newspaper Il Secolo XIX. In the summer of 1915 she went to Berlin from where she sent daily dispatches under the pseudonym of Mario Valeri. In the autumn of 1915 the Italian Supreme Command granted Steno permission to visit the medical formations on the front. Under the headline “Nell’orbita della guerra” she published a series of articles in Il Secolo XIX about the organization of healthcare in the Italian army. Her strong nationalism and anti-German sentiment found expression in the book Il Germanesimo senza maschera (Germanism without a mask), published in 1917. In 1919, Steno returned to Berlin to witness the aftermath of the war. Moreover, she attended the Paris peace conference as a correspondent.

Wanda Zembrzuska (1889-1945) was a Bulgarian journalist of Polish descent. During the war she reported as a war correspondent for various Bulgarian and Polish newspapers, among them Otro/Utro, Dnevnik and Mir. In August and September 1915 Zembrzuska witnessed the Gallipoli campaign. She was accredited to the Fifth Ottoman Army and reported for the Bulgarian newspaper Otro. Her accounts focus more on the events behind the front than on the actual battles and shed light on the Turkish experience of the war. She met with General Otto Liman von Sanders, the Imperial German Army general and commander of the Fifth Ottoman Army. Her accounts provide information about the administrative structure of the Fifth Army Headquarters under Liman. In 1916 Zembrzuska reported from Greece and from the Romanian-Bulgarian front for the Lviv (Lwów, Lemberg) newspaper Gazeta Wieczorna.

Alice Schalek (1874-1956) was an Austrian journalist, travel writer and photographer. During 1915-1917 she was accredited to the Austro-Hungarian War Press Office and undertook journeys to the Austro-Italian front, to Galicia, and to Serbia. Schalek published dozens of war reports in the Viennese daily Neue Freie Presse. Moreover, the popular illustrated weekly Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung printed several photographs and photo essays. Schalek wrote two books and drew an enthusiastic audience to her war lectures. In February 1917, she was awarded a medal for her propagandistic mission in the service of the Monarchy. Her war reporting was highly acclaimed by her contemporaries, but also sharply criticised for its lack of objectivity and tendency to glorify and romanticise the war. The War Press Office, however, disapproved of Schalek’s increasingly honest reporting, which had the potential of demoralising the public. She was dismissed in September 1917. Schalek’s war photographs can be found digitised on the website of the Austrian National Library.

Nellie Bly (1864-1922, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane Seaman) was an American journalist. She won fame for her record-breaking trip around the world in 72 days and for her undercover journalism. When the First World War broke out, she went to Austria due to financial problems at home. On her own initiative she was accredited by the Austro-Hungarian War Press Office and spent several weeks in October and November 1914 on the Eastern Front in Poland, Galicia and Serbia. She published her accounts in various American papers (via the Hearst International News Service). Between December 1914 and February 1915, 21 articles appeared in the New York Evening Journal under the headline “Nellie Bly on the Firing Line”. Her articles painted a grim picture of the cruelty of modern warfare. Bly also published a report in Die Zeit. This, however, was severely cut by the newspaper and thereafter Bly refused to write further articles for the German paper. For the remainder of the war Bly worked for Austrian charities helping widows and orphans.

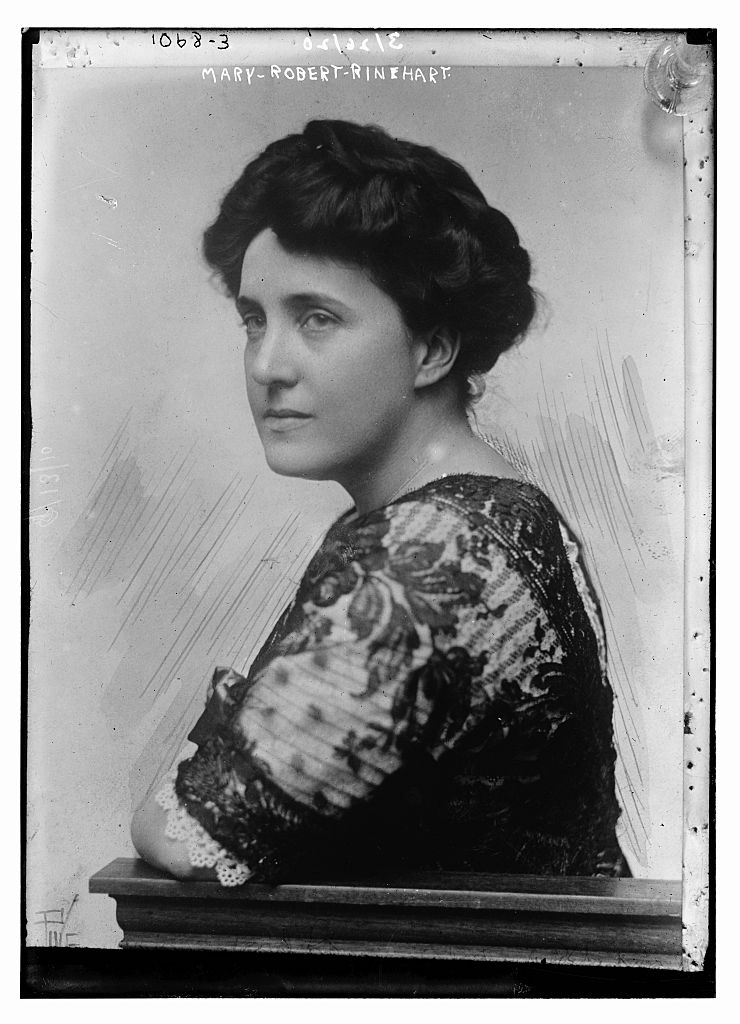

Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958) was a popular American author of crime fiction and a trained nurse. She regularly contributed to the illustrated magazine Saturday Evening Post (America’s largest paper). During the war she was attached to the Belgian Red Cross and visited the Belgian and French sectors as well as British lines on the Western Front in 1915. Rinehart was able to see trenches, shelled towns and no man’s land. Her endorsement with the Belgian Red Cross opened her the door to interviews with the exiled Belgian King Albert I, Queen Mary of England, and commanders of the French and British armed forces. Rinehart published her reports in the Saturday Evening Post, Boston Globe and The Sphere. They were gathered in her book Kings, Queens and Pawns (1915).

Inez Milholland Boissevain (1886-1916) was an American labour lawyer, socialist reformer, pacifist and leading suffragist writing for the New York Tribune, Chicago Daily Tribune, Washington Post, McClure’s and Harper’s. During the war, the New York Tribune sent her to Italy to cover the war. In the summer of 1915 she took part in a guided tour of correspondents to the Italian front. However, the Italian authorities disliked her anti-war articles. At the end of September 1915 she was ordered to leave the country. The New York Times reported on 28 Sept 1915 that the Italian government thought it “not politic to have war presented from a pacifist point of view”. She died in 1916, aged 30, of pernicious anemia while on a speaking tour to campaign for women’s right to vote as a member of the National Women’s Party.

Eleanor Franklin Egan (1879-1925, Bertha Eleanor Pedigo) was an American journalist and foreign correspondent. She reported on the First World War and its aftermath for the popular illustrated magazine Saturday Evening Post. She had previously covered the Russo-Japanese War and the Russian Revolution of 1905 for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. In November 1917 she travelled to the fighting zone of Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) to report on the British war effort. She took the route via Singapore to Bombay and then to Basra and Baghdad. On her way back to the USA she also travelled via India. In 1918 she published The War in the Cradle of the World, a book based on her articles about the war in Mesopotamia. During the war, Egan also reported from Belgium, Serbia, Armenia and Turkey. After the end of the war, Egan continued to report on conflict zones. Cases in point are the famines during the Russian Civil War and in China during the 1920s.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Harriet Chalmers Adams (1875-1937) was an American explorer, geographer, journalist, photographer and lecturer. She published accounts of her journeys in the National Geographic Magazine. In 1916 she went to France as a war correspondent for Harper’s Monthly Magazine, touring the Lorraine region for three months. She was allowed to visit and photograph the French trenches during a French army tour. She visited American hospitals and munition factories, where women were replacing the male workforce. Moreover, she documented the impact of the war on the French civil population. Hidden in a cellar, she experienced the shelling of a French town by the Germans. Adams published a long illustrated account of her visit to the front in the National Geographic Magazine in November 1917.

Marylie Markovitch (1866-1926, Amélie de Néry) was a French journalist, writer, poet and feminist. During 1915-1917 she was a special correspondent (the first woman) of Le Petit Journal and Revue des deux mondes. She also served as a Red Cross nurse on the Eastern Front in Russia and witnessed the Russian revolution in St. Petersburg. She reported about her experiences in numerous articles and was mentioned frequently in the French press. Many newspapers reprinted her articles. In 1918 she published her Russian experience in the book La Révolution Russe vue par une Française.

Avis Waterman (born ca. 1880), an American journalist, was the London Times’ Milan correspondent during from 1915 to 1920. She was also accredited to the Italian army and undertook several visits to the Italian front in the Alps. Waterman’s longer dispatches in The Times remain anonymous (labelled ‘From our Milan Correspondent’). In the shorter reprints of her reports in Australian and New Zealand papers she was acknowledged as ‘Mrs. Waterman, the “Times” correspondent at Milan’. Contemporaries praised Waterman for her courage and journalistic skills. In November 1917 the New Zealand Free Lance called her one of the longest serving war correspondents of the First World War. The the Alpini, the Italian mountain fighters, decorated Waterman with the Italian Cross of War.

Wikimedia Commons

Dorothy Lawrence (ca. 1896-1964) was a young English woman who unsuccessfully tried to become a war reporter. In 1915, aged 19, she travelled on her own initiative to France and entered the British sector on the Somme with forged identity papers and disguised as a male soldier in khaki uniform. For ten days she worked with a specialist mine-laying company. After her arrest and interrogations by military authorities, Lawrence was sent back to England and forbidden to write about her adventure. In 1919 she did publish an autobiographical account, Sapper Dorothy Lawrence, the only English Woman Soldier. This, however, was heavily censored by the War Office and not the hoped-for commercial success. With no income and her mental health deteriorating, Lawrence was declared insane in 1925 and admitted to a psychiatric institution where she remained until her death.

Louise Mack (1870-1935) was an Australian novelist, poet and journalist. She reported for the British newspapers Daily Mail and Evening News about the German invasion of Belgium in 1914. When the war broke out she managed to get into occupied Belgium. She travelled through German lines and was in Brussels, Louvain and Antwerp. According to her own account, she left Antwerp on a false passport and disguised as a hotel maid. In 1915 she published her eyewitness account A Woman’s Experiences in the Great War. In 1916, Mack returned to Australia. During 1917-18 she toured the country, speaking about her experiences and raising money for the Australian Red Cross Society. Mack’s accounts of her experiences in wartime Belgium were sensationalist and embellished; as a speaker in Australia she was hugely popular.

Carmen de Burgos (1867-1932) was a well-known Spanish novelist, travel writer, translator, teacher, women’s rights activist, journalist and editor of El Diario Universal. She was the first Spanish female war correspondent, reporting on the Spanish-Moroccan conflict in 1909 and on the First World War. The latter broke out while she was travelling through Germany in August 1914. She was detained in Germany and accused of being a Russian spy, before being able to return to Spain. During a second trip in 1916-17 she stayed in Paris, visiting a hospital for the blind, among others. De Burgos published her war accounts, which reveal her anti-war sentiment, under the pseudonym “Colombine” in El Heraldo de Madrid. Later they were gathered in the second volume of her book Mis viajes por Europa (1917). De Burgos was the first woman to appear on the list of forbidden authors under Franco.

Annie Åkerhielm (1869-1956) was a Swedish writer and journalist and a campaigner against women’s suffrage and democracy. In 1916 she and her husband were invited to Berlin. The same year she published the book Från Berlin till Brüssel about her war journey. Åkerhielm was pro-German and convinced that Germany was the only warring power without guilt for the outbreak of the war. In her book she idealised the Germans and described the German invasion of Belgium as an act of self-defence forced by bitter necessity. Åkerhielm also published a long article about conditions in wartime Germany in the Leipzig Illustrirte Zeitung. It depicted Berlin as calm and focused on the war, while the social and cultural life was continuing as in peacetime. Åkerhielm was critical of the Versailles treaty with its harsh treatment of Germany. Later became an admirer of National Socialism and Adolf Hitler.

Stefania Türr (1885-1940) was an Italian writer and journalist of Hungarian origin. In 1917 she spent 12 days at the front as a war correspondent for the monthly magazine La Madre italiana (The Italian Mother), which she had founded in 1916. She visited the fighting lines and talked to the soldiers about their war experiences. Türr also met with high-ranking officers and with King Vittorio Emanuele III. After her return, she wrote Alle Trincee d’Italia (At the Trenches of Italy), an account of her visit to the front. The book aimed to rouse the admiration of her readers for the brave Italian soldiers. It is enriched with numerous photographs (reprinted with permission from the Italian High Command). Little is known about Türr’s life in the interwar years. Leaning towards Fascism, she continued her career as a writer and died in Florence in 1940, aged 55.

Matilde Serao (1856-1927) was a renowned Italian writer, journalist and founder and editor of the newspaper Il Giorno. During the war, Serao remained on the home front. Her journalism focused on the human side of the war, and in particular on the contribution of Italian women to the war on the home front. Military battles are not mentioned. Serao gathered her articles, which originally appeared in Il Giorno in 1915 and 1916, in the book Parla una donna (1916). The book is dedicated to her three sons serving at the front and addressed to Italy’s women. It pays tribute to the heroism of the women who replaced men in all fields of the economy and whose lives were fundamentally transformed by the war. In her war writings Serao adhered to the traditional figure of mother and wife. Her journalism is important not only because of its focus on the impact of the war on women. Serao also addressed the book specifically to a female, middle-class audience that shared her feelings and observations.

Illustriertes Mittwochblatt, supplement of Leitmeritzer Zeitung, 4 July 1917

Thea von Puttkamer (1882-1952) was a German novelist and journalist. During the First World War she was based in Constantinople (Istanbul). As a member of the German ambulance corps in Turkey she was attached to the Turkish forces. Her reports appeared in German, Hungarian and Turkish newspapers (Frankfurter Zeitung, Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, Die Woche, Pester Lloyd, Vakit). They were also reprinted in German-American newspapers, among them a report on the Gallipoli campaign. In the autumn of 1918 she witnessed the retreat of the Ottoman army in Palestine. In August 1917, the South Carolina Union Times reported that von Puttkamer, “attached to the Turkish forces operating in Mesopotamia, is the only woman war correspondent officially recognized by the German government”. However, information about von Puttkamer is scarce.

Margit Vészi (1885-1961) was a Hungarian novelist, journalist, painter and photographer. During 1915-1918 she was accredited to the Austro-Hungarian War Press Office and reported from the Italian front. Her articles appeared in Az Est, Pesti Napló, Pester Llyod, Neue Freie Presse, Neues Wiener Tagblatt, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and others. They were gathered in two books, Az égö Európa (1915) and Útközben (1918), which received favourable reviews. Her war reports focused less on battles. Rather, they were rather an impressionist description of everyday military life and of the landscapes affected by the war. In 1917 she was accredited to report from the Stockholm peace conference. During the war, Vészi frequently gave war lectures illustrated with slides of her own photographs from the front.

Mary Boyle O’Reilly (1873-1939) was an Irish-American social reformer, writer and journalist. In 1913 she became the foreign correspondent of the Newspaper Enterprise Association. After assignments to Mexico and Russia, she was placed in charge of its London office. When the war broke out, O’Reilly was sent to Belgium to write about the human side of the war. She entered occupied Louvain disguised as a peasant refugee and was the first American journalist to witness the city’s burning by the Germans. Still in disguise, she walked around Belgium, passing through German lines and writing her notes on her white blouse. After five weeks in Belgium, O’Reilly returned to London. In the following months and years she travelled to France, and via Norway and Sweden to Russia (St. Petersburg, Moscow), Lithuania and Poland (Warsaw), reporting the war on the Eastern Front. During her travels in Europe, O’Reilly’s war reports appeared in various American newspapers.

Louise Bryant (1885-1936) was an American suffragist, political activist and journalist writing for various newspapers. During the war she and her second husband, the journalist John Reed, went to Moscow and St. Petersburg and covered the Russian Revolution in 1917. Bryant’s assignment was to report on the war from a woman’s perspective; her reports were distributed by the Bell Syndicate. In 1918 she published a collection of her articles as Six Red Months in Russia. After her return to the United States, Bryant continued to campaign for feminist and socialist causes. She supported the Bolshevik Revolution before a congressional sub-committee and in her public lectures. She returned to Russia in 1920, where her husband died. In the following years Bryant continued to travel through Europe, writing about Russia, Turkey, Italy and other countries. She died in Paris in 1936.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

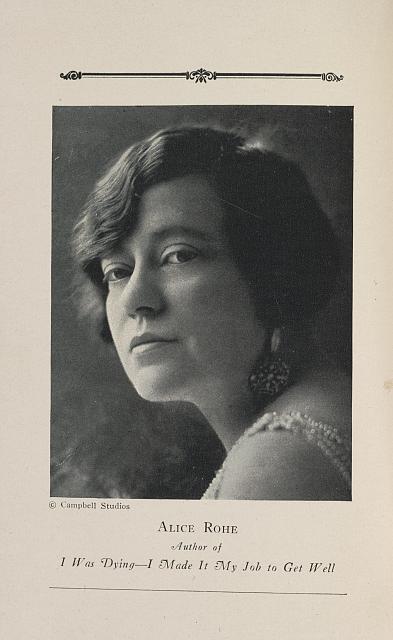

Alice Rohe (1876-1957) was an American author, journalist, photographer and feminist. During the First World War she served as the first female overseas bureau chief for the American news agency United Press in Rome. She was also a correspondent for the Exchange Telegraph of London. In October 1914, Rohe briefly reported from Vienna. Unlike many of her foreign colleagues, who waited for Italians to tell them what was happening, Rohe went into the Italian countryside to gather news directly. She wrote stories, illustrated with her own photographs, about the war’s impact on civilians. They appeared in the New York World, Denver Times, Washington Post, Leslie’s Weekly and National Geographic Magazine. She was twice accused of being a spy.

Peggy Hull (1889-1967, Henrietta Eleanor Goodnough Deuell) was an American writer and journalist who covered both World Wars. In November 1918, after the end of the war in Europe, she became the first American female war correspondent officially credentialed by the US War Department. Subsequently, she continued to report on the Russian Civil War and American troops in Siberia. In 1917 she had been denied official accreditation and went to France on her own expenses. The Paris army edition and the Chicago edition of the Chicago Tribune, the El Paso Morning Times, and the Newspaper Enterprise Association published her accounts. Through personal connections, including General Pershing, she gained privileged access to an American artillery training camp in France. Hull’s articles were very popular in the United States because she presented personal stories of the lives of soldiers.

Helen Johns Kirtland (1890-1979) was a photojournalist working for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. During the First World War she photographed in France, Belgium and Italy. She showed particular concern to document women’s war work and the destruction brought about by the war. After the retreat at Caporetto in 1917, where 275,000 Italian troops had been captured, the Italian High Command granted Kirtland permission to visit the frontline. In the autumn of 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian and the Italian armies again confronted each other, Kirtland was granted special access to the front. There she photographed Italian soldiers in the trenches. In 1919 Kirtland and her husband photographed the Versailles peace conference.

Further Reading

Seul, Stephanie: “Women War Reporters”, in Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson (eds.), 1914-1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2019. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11385.