By Camilla Giordano and Stephanie Seul

The Italian journalist and writer Stefania Türr was born in Rome in 1885. She was the daughter of the Hungarian soldier, revolutionary and engineer István Türr, known in Italy as Stefano Türr and remembered for his role in the Risorgimento. She inherited her father’s bravery, combative spirit, and glowing patriotism.

La Madre Italiana

In 1916, Stefania Türr founded the association Madri italiane a tutela degli orfani di guerra (Italian Mothers Protecting War Orphans) and the monthly journal La Madre Italiana. Rivista femminile pro orfani di guerra (The Italian Mother. Women’s Magazine pro War Orphans), published in Milan until 1919. From its inception, Türr wrote most of the articles. The small-format magazine quickly became popular and drew a distinguished readership including Queen Margherita. La Madre Italiana was not only a point of support for Italian mothers, who were invited to write to the magazine and have their opinions published, but also a tool for interventionist propaganda (i.e. propaganda in favour of Italy’s entry into the war). The magazine overturned female pietas, legitimising male violence in defence of the fatherland, and urged Italian women to take a stand and play an active role in the war. According to Türr, women should be like the mothers of Sparta in ancient Greece who sent their sons off to war with honour and pride. Thus, motherhood became a means of emancipation – being a mother meant participating actively in the war and in society.

Despite having an eleven years old son, in June 1917 Türr went on a 12 day trip to the front as a war correspondent for La Madre Italiana. She was accompanied by the journal’s secretary, Rina Cavallazzi. Her repeated requests to visit the front had initially been rejected by the Italian high command. Türr was driven by a desire to bring to the Italian soldiers in the trenches the greetings of their mothers, brides, wives and sisters, and to listen to the soldiers’ war stories (Alle trincee d’Italia, pp. 26-27). Through her visit to the trenches, Türr felt empowered as a woman. Her longing to fight in the war was strong. Before leaving for the front, she phantasised:

in Türr, Alle trincee d’Italia.

Photo: Stephanie Seul

It seemed to me that I was no longer a weak woman, who went among the soldiers only to do moral work. Rather had I to leave [for the front] to take command of a regiment, to face the real war […].

Türr, Alle trincee d’Italia, p. 29

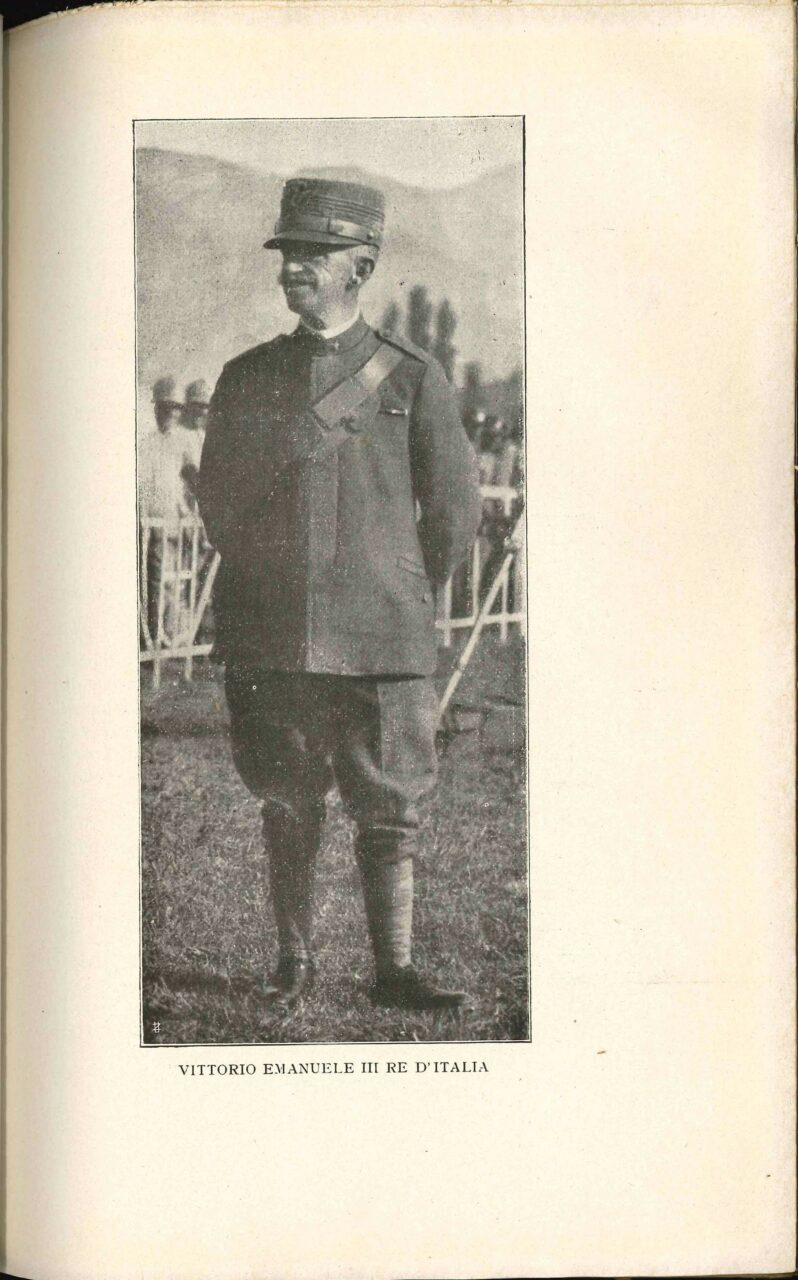

If it had been possible for a woman, Türr would have participated in combat. Instead, she was content with visiting the fighting lines and talking to the soldiers about their war experiences. Türr also met with high-ranking officers, among them the Chief of Staff of the Italian Army, General Luigi Cadorna, and General Carlo Porro, Senator of the Kingdom of Italy, and with King Vittorio Emanuele III.

Türr narrated her impressions of the front and her feelings about the war in La Madre Italiana in July 1917: “And so we spent twelve days of intense, feverish life, full of emotions, full of shudders, full of wonderful sensations.” (“’La Madre Italiana’ al fronte”, p. 7) Moreover, she published two books about her experience: Alle Trincee d’Italia: note di guerra di una donna (At the Trenches of Italy: A Woman’s War Notes) appeared in December 1917, I soldati d’Italia. Racconti della guerra (The Soldiers of Italy. Tales of the War), in the summer of 1918.

Alle trincee d’Italia

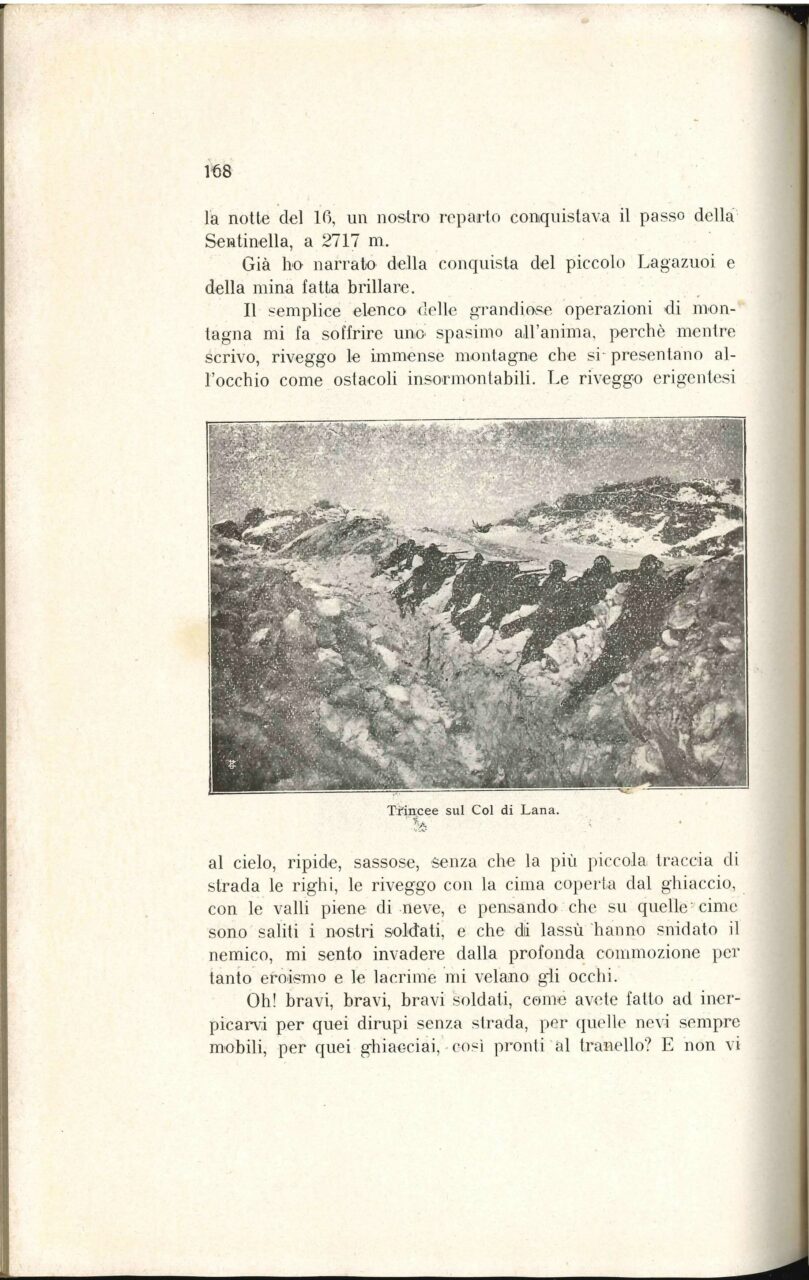

Alle trincee d’Italia is an eyewitness account of what Türr saw and felt at the front. Although factual and detailed, it is imbued with empathic words, patriotism, and war propaganda. Countless adjectives inflate the story. Through Türr’s eyes, the readers see the various sections of the Italian front in north-eastern Italy: the Carso, San Michele, Monte Nero, Caporetto, the Calvario, Sabotino, Monfalcone, Gorizia, Aquileia, and the Alpine frontline in the Trentino. Türr pays particular tribute to the brave fighting of the Alpini, the Italian Army’s specialist mountain infantry corps, who had to cope with fierce cold and snow.

Türr’s account is geographically flawless and enriched with numerous photographs (reprinted with permission from the Italian High Command). A patriotic and interventionist vein is the lens through which Türr describes the war and life in the trenches. Türr often uses the word impressioni (impressions), which has a subjective connotation and implies emotional involvement. The linguistic choice indicates the author’s desire to tell not only what she saw at the front, but also the strong personal feelings that her war experience evoked.

I soldati d’Italia

In the summer of 1918, Stefania Türr published the children’s version of her war account: I soldati d’Italia. This book was written with a pedagogical and propagandistic intent. It explained the causes of the First World War and the development of the conflict with the aim of furthering patriotic education. Türr addressed the children in the first pages:

Photo: Stephanie Seul

I have seen all these things, and I will tell you all about them. Listen to me carefully, because I want you to have a clear idea of why the war had to be fought, why my father had to leave [Stefano Türr left home and children in order to fight in the Italian wars of independence], of why the whole Italian nation has risen up in arms. And finally, I want you to know all about the great beautiful deeds of the soldiers.

Türr, I soldati d’Italia, p. 11

Türr uses the verb ricordate (remember) in the imperative form numerous times, inviting (or rather, commanding) the children to keep alive and pass on the memory of the achievements of the Italian soldiers in the war.

Like Alle trincee d’Italia, I soldati d’Italia reprinted photographs with permission from the Italian High Command. They depict the theatres of war, the king, and leading officers of the Italian army. Some photographs are identical with those reprinted in Alle trincee d’Italia. If the first book is a subjective war reportage, the second recites a patriotic fairy tale in which the brave Italian soldiers fight the “evil”. Türr aims to rouse the children to be proud of the Italian army, of Italy, and of being Italians.

Some chapters on the Italian theatres of war bear the same title in both books, although their content is different. However, the style, full of adjectives and words that express love for the fatherland and infinite admiration for the soldiers, is similar in both works. In the prefaces, Türr exclaims: “Long live Italy, long live the soldiers of Italy”. The last page of each book shows an advertisement for the journal La Madre Italiana.

Identical photo in Türr, I soldati d’Italia, p. 23

in: Türr, Alle trincee d’Italia, p. 168.

Photo: Stephanie Seul.

Identical photo in Türr, I soldati d’Italia, p. 49

Stefania Türr was undoubtedly a passionate and courageous journalist. Motherhood and a glowing patriotism shaped her Weltanschauung. Although her war reports cannot be considered an objective record, they nevertheless are important testimonies from a socio-cultural point of view. They help us understand the condition of Italian women in the early Twentieth Century. Stefania Türr gave a voice to women, claiming an active role in society and equality between the sexes. She felt like a warrior, a soldier.

Little is known about Türr’s life after the First World War. Leaning towards Fascism in the interwar years, she continued her career as a writer and published several books, among them a travelogue, a biography of her father Stefano Türr, and volumes about automobiles. She died in Florence in 1940, aged 55.

Further Reading

War Publications by Stefania Türr

La Madre Italiana: Rivista femminile pro orfani di guerra (Milano, 1916-1919) [volumes of 1916 and 1917 digitised]

Türr, Stefania: Alle trincee d’Italia: Note di guerra di una donna. Libro di propaganda illustrato con fotografie concesse dal Comando Supremo. Milano: A. Cordani, 1917.

Türr, Stefania: I soldati d’Italia: Racconti della guerra. Libro di propaganda illustrato con fotografie concesse dal Comando Supremo. Firenze: Bemporad e Figlio, 1918.

Other Publications by Stefania Türr

Türr, Stefania: I viaggi meravigliosi: Danimarca, Norvegia, Spitzberg, Svezia, Finlandia. Milano: A. Cordani, 1926.

Türr, Stefania: L’opera di Stefano Türr nel Risorgimento italiano (1849-1870) descritta dalla figlia. Firenze: Tipografia fascista, 1928.

Türr, Stefania: Le impressioni di una automobilista. Firenze: Tipografia L. Franceschini, 1930.

Türr, Stefania, and Roberto Sgrilli: Il collaudo della “Colombina due”. Firenze: Bemporad e Figlio, 1931.

Secondary Literature

Frattolillo, Angela: I ruoli della donna nella Grande Guerra. Sonciniana: Fano, 2015.

Guidi, Laura (ed.) Vivere la guerra: Percorsi biografici e ruoli di genere tra Risorgimento e primo conflitto mondiale. Napoli: ClioPress, 2007.

Molinari, Augusta: Una patria per le donne: La mobilitazione femminile nella Grande Guerra. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino, 2014.

Soglia, Nunzia: “Il racconto dal fronte: il reportage di Stefania Türr.” In Umberto Rossi (ed.), Guerra, intercultura, transcultura, special issue of Studi Interculturali 3 (2015), pp. 15-28.

Soglia, Nunzia: La Grande Guerra raccontata dalle donne. Salerno: Edisud Salerno, 2016, pp. 23-39.

Tagliaventi, Federica: “Un’inviata al fronte: Stefania Türr.” In: Marta Boneschi et al. (eds.), Donne nella Grande Guerra. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino, 2014, pp. 137-48.