By Camilla Giordano and Stephanie Seul

Matilde Serao, Flavia Steno and Stefania Türr were prominent figures of Italian journalism who, through newspaper articles and books, narrated the First World War from the female perspective. The conflict that devastated Europe also became a pretext for talking about the role of women during the war and the obstacles they faced in early twentieth-century Italy.

In 1916, Matilde Serao wrote Parla una donna (A Woman Speaks), an account of the home front. In contrast, Flavia Steno and Stefania Türr went to the front as accredited war correspondents and personally experienced the war. Both recounted their experiences in newspaper articles and books.

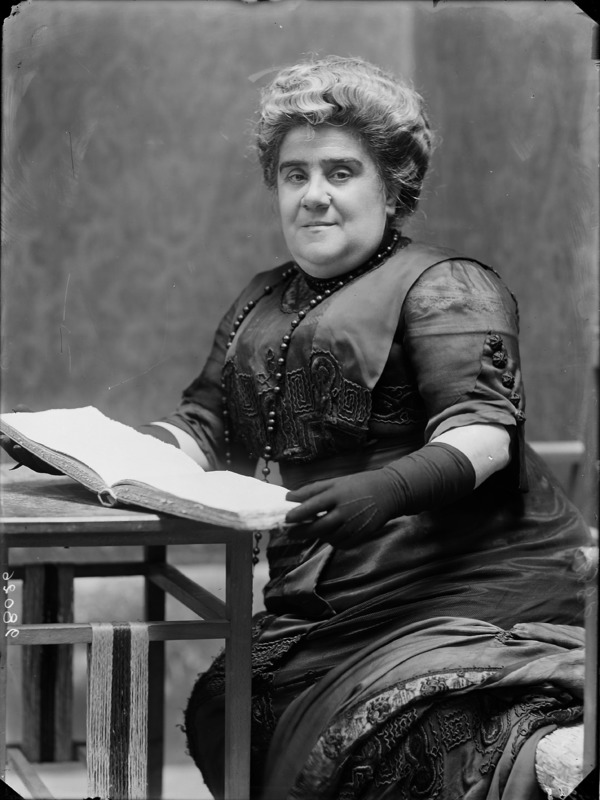

Matilde Serao (1856-1927)

Matilde Serao was born in 1856 in Patras, Greece, where her father was in exile for political reasons. Her mother was an impoverished Greek noblewoman. When Serao was still a child the family returned to Naples. Serao was the first Italian woman to co-found and edit a daily newspaper, Il Corriere di Roma. In 1892 she also founded Il Mattino and in 1903 Il Giorno, which she edited until her death. Serao wrote 26 novels and 160 novellas. She was a cornerstone of bourgeois journalism and her colourful language the result of a self-taught process.

During the First World War, Serao remained on the home front. In her war writings she focused on the human side of the war. In contrast, the battles of 1915 and 1916 are not mentioned. Instead she emphasised the strength and courage of the Italian soldiers and praised the individual who represented the people.1Zangrandi, Silvia: “Una donna che parla alle donne: La Prima guerra mondiale vista da Matilde Serao in ‘Parla una donna’.” In Cuadernos de Filología Italiana 22 (2015), pp. 195-214, here pp. 201-202. Her articles, which were originally published in Il Giorno in 1915 and 1916, were gathered in 1916 in the book Parla una donna andprovide a sociocultural portrait of the time. An embryonic feminism emerges, defined by Elisabetta Rasy as “anti-emancipationist feminism”.2Rasy, Elisabetta: “’Parla una donna’: Il diario di guerra di Matilde Serao.” In Chroniques italiennes 39-40 (1994), pp. 243-254. On 6 April 1887 Serao had written in Il Corriere di Roma:

The woman must not have a political opinion; she can be, at most, monarchical, thus, out of an instinct for peace, out of a feeling of devotion, but she must not allow herself to make profession of political faith, never in public. And this for the great reason of women’s poetry: poetry that comes from silence and reserve, from a high sense of decorum, from a constant love of honest and noble things. The moral field in which the female intellect and heart can dignifiedly manifest itself is very vast; it is useless, it is ridiculous, it is harmful for her to descend to the vulgarity, mediocrity, and the low trifles of politics.3Quoted in Nadia Verdile: “Matilde Serao, la femminista antifemminismo”, 20 July 2019, https://vitaminevaganti.com/2019/07/20/matilde-serao-la-femminista-antifemminismo/ (accessed 25 November 2021).

Moreover, in an interview with Alfredo Capuano in 1904, Serao had argued that

Feminism does not exist, there are only economic and moral issues that will dissolve or improve when the general conditions of mankind improve. (…) Ensuring women’s sacrosanct right to live, giving them the means to exercise it, that, if I accept the word, is feminism.4Quoted in ibid.

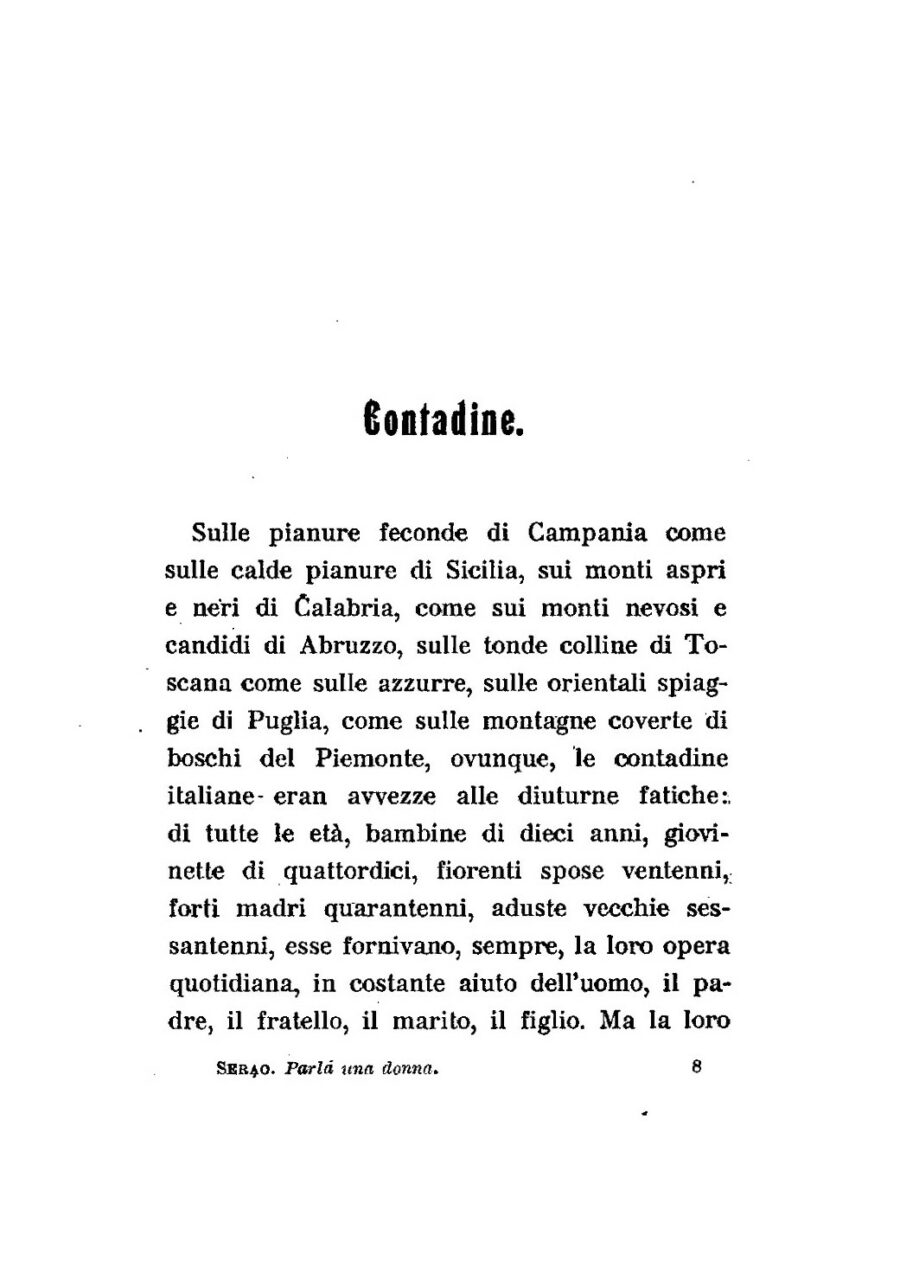

In her war writings Serao adhered to the traditional figure of mother and wife. Parla una donna was addressed to Italy’s women (“mie sorelle di pena” – “my sisters in sorrow”). It offers them comfort by constantly celebrating the feminine virtues of mothers, brides and sisters who sacrificed themselves silently. Sarao praised the Italian women who worked in factories and fields replacing the men who had left for the front. Fundamental to understanding Serao’s mindset is the chapter “Contadine” (Peasant Women), dedicated to the country women, recounting how they constantly added male labour to their already heavy daily burden of childcare, housework and animal care, because their husbands, sons and fathers had departed for the war.

Matilde Serao had a challenging relationship with power, even in the last years of her life. She was an anti-Fascist and in 1926, shortly before her death, wrote Mors Tua, an anti-war novel that earned her a nomination for the Nobel Prize for Literature, which was however given to Grazia Deledda for political reasons. Silvia Zangrandi writes: “We know that Serao was against war, and she reiterated this in 1926 when she published Mors tua where she polemised against the war of 1915-18 and against all wars. It has been said that her pacifism was humanitarian, not political, and if she accepted war, it was only out of patriotic duty.”5Zangrandi, Silvia: “Una donna che parla alle donne: La Prima guerra mondiale vista da Matilde Serao in ‘Parla una donna’.” In Cuadernos de Filología Italiana 22 (2015), pp. 195-214, here p. 211.

Flavia Steno (1877-1946)

Flavia Steno (pen name for Amelia Cottini Osta), was born in 1877 in Lugano, Switzerland, to a family of Savoy origins. She attended university in Zurich and later lived and worked in Genoa. After graduating she started working for the Genoese newspaper Il Secolo XIX, first as a journalist and then as a writer of serial novels. During the First World War she was one of few Italian female journalists admitted to the Italian frontline on Mount Krn (Monte Nero) as official war correspondent for Il Secolo XIX.6Pisano, Laura (ed.): Donne del giornalismo italiano. Da Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel a Ilaria Alpi. Dizionario storico biobibliografico. Secoli XVIII-XX. Milano: Franco Angeli, 2004, p.139; Carla Gubert: “‘We are exiting the realm of life, for real, to enter the theatre of war’: Flavia Steno’s reports from the front.” In Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 21,2 (2016), pp. 252-270.

In the summer of 1915 Flavia Steno went to Berlin from where she sent daily dispatches under the pseudonym of Mario Valeri. Her knowledge of German allowed her to mingle among the people and to listen to the voices revealing the war conditions in Germany. However, Steno was also aware of, and embittered about, the disadvantage of being a woman. On 5 February 1917 she wrote in a letter to Mario Perrone, the editor of Il Secolo XIX:

I am a woman, I cannot even sign everything I write because I myself am the first to recognize that it would not be appropriate to put a woman’s name at the bottom of any article.7Quoted in Picchiotti, Antonella: Flavia Steno: Una giornalista, una donna (1875-1946). Genoa: Frillieditori, 2010, pp. 168

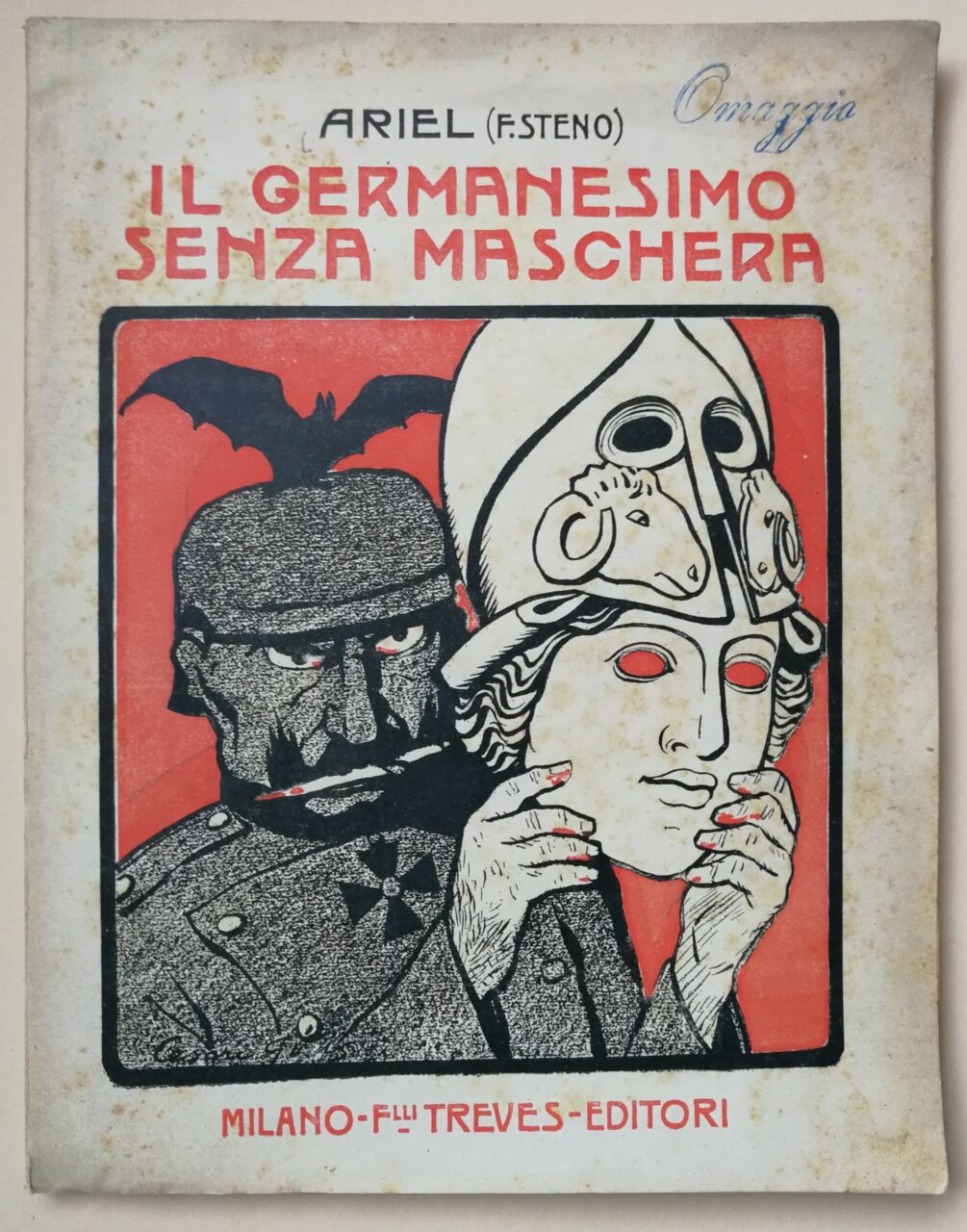

Throughout the war, Flavia Steno used various pseudonyms: While in Berlin, she wrote under the name of Mario Valeri. Her volume Il Germanesimo senza maschera (1917) was signed “Ariel” and “F. Steno”. And her book Per non dimenticare (1919) appeared under the pseudonym of “Mauro Deni”.8Stolfi, Valeria: “Amelia Osta Cottini detta Flavia Steno (Lugano 1877 – Genova 1946).” In: Enciclopedia delle donne, online: http://www.enciclopediadelledonne.it/biografie/amelia-osta-cottini/ (accessed 29 November 2021). In contrast, her booklet Guerra di popolo (1917), a propagandistic text in favour of interventionism, was published under her own name.

Scrupulous military censorship required journalists during the First World War to reassure readers about the good conditions of the army. For this reason, in October/November 1915 Steno went to Palmanova to obtain permission from the Supreme Command to visit the military health organisation on the front. Under the headline “Nell’orbita della guerra” (In the Orbit of War) she published in Il Secolo XIX a series of articles about the organization of healthcare in the Italian army.9Picchiotti, Antonella: Flavia Steno: Una giornalista, una donna (1875-1946). Genoa: Frillieditori, 2010, p. 175; Carla Gubert: “‘We are exiting the realm of life, for real, to enter the theatre of war’: Flavia Steno’s reports from the front.” In Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 21,2 (2016), pp. 252-270.

In addition to an explicit invitation to pietas, from Steno’s articles emerges a strong patriotism that flows into a warlike and pompous anecdotal style. Unlike Serao, Steno was an interventionist. From 6 May to 28 September 1916, she edited the series “Il Germanesimo senza maschera” (Germanism without a mask), a nationalist and economic campaign against Germany which compared the “German danger” to an octopus. The series was published in 1917 as a book under the same title. In 1919, Steno returned to Berlin to witness the aftermath and the consequences of the war. Moreover, she attended the Paris peace conference as a correspondent.

Steno’s verdict on fascism was harsh. On July 27, 1944, she was sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment following the publication of her opinion on children’s textbooks in Il Secolo XIX in 1943, in which she opposed the Fascists (“it is not excessive to judge them as an abomination”). Forced to leave Genoa, she found refuge in a farmhouse in Moncalvo, where partisans were staying. By obtaining a false identity card she waited for the fall of the regime. In 1946, shortly before her death, she returned to writing.10Stolfi, Valeria: “Amelia Osta Cottini detta Flavia Steno (Lugano 1877 – Genova 1946).” In: Enciclopedia delle donne, online: http://www.enciclopediadelledonne.it/biografie/amelia-osta-cottini/ (accessed 29 November 2021).

Steno, like Serao, was an anti-Fascist, a woman of great charismatic appeal, and a “non-feminist feminist”. She was a member of the Ligurian Association of Journalists, of the Women’s Association, and she wrote throughout her life for the periodical La Fronde, edited only by women.

In the article “Le donne in guerra” (Women at war) in the “Note e Macchiette” column (Il Secolo XIX, 19 December 1915) Steno praised the Italian women who replaced men in agriculture and in the factories and helped the soldiers at the front as nurses and doctors).11Picchiotti, Antonella: Flavia Steno: Una giornalista, una donna (1875-1946). Genoa: Frillieditori, 2010, p. 180.

While maintaining a moderate tone in regard to feminism, Steno dealt with crucial issues such as the lawfulness of advocacy for women. In November 1919 she founded the women’s magazine La Chiosa. However, the journalist, like Matilde Serao, was not in favour of the female vote because she considered the Italian woman not yet ready at a cultural level.

Stefania Türr (1885-1940)

Stefania Türr born in Rome in 1885. Her father was the Hungarian soldier and politician István (Stefano) Türr, fighter in the wars of independence and known for his role in the Risorgimento. In 1917, Stefania Türr went to the front as a war correspondent for the monthly magazine La Madre italiana. Rivista femminile pro orfani di guerra (The Italian Mother. Women’s Magazine pro War Orphans), which she had founded in 1916. Motherhood played a key role in Türr’s thinking. Influenced by her father’s military past, she urged women to take a stand against the Austrian and German enemies. According to Türr, women should be like the mothers of Sparta in ancient Greece who sent their sons off to war with honour and pride. Unlike Serao and Steno, Türr was in favour of women entering politics, claiming in strong and sententious tones the equal rights of men and women. In 1918 she wrote in La madre italiana:

In the days of feverish work, in the days of trepidation and pain, you called us, we rushed in and gave you the necessary and fruitful help. We can no longer be absent from the political life of nations and you must provide.12“Questioni femminili.” In La madre italiana, III, 10, 1918, p. 380, quoted in Frattolollo, Angela: I ruoli della donna nella Grande Guerra. Fano: Sonciniana, 2015, pp. 47-48.

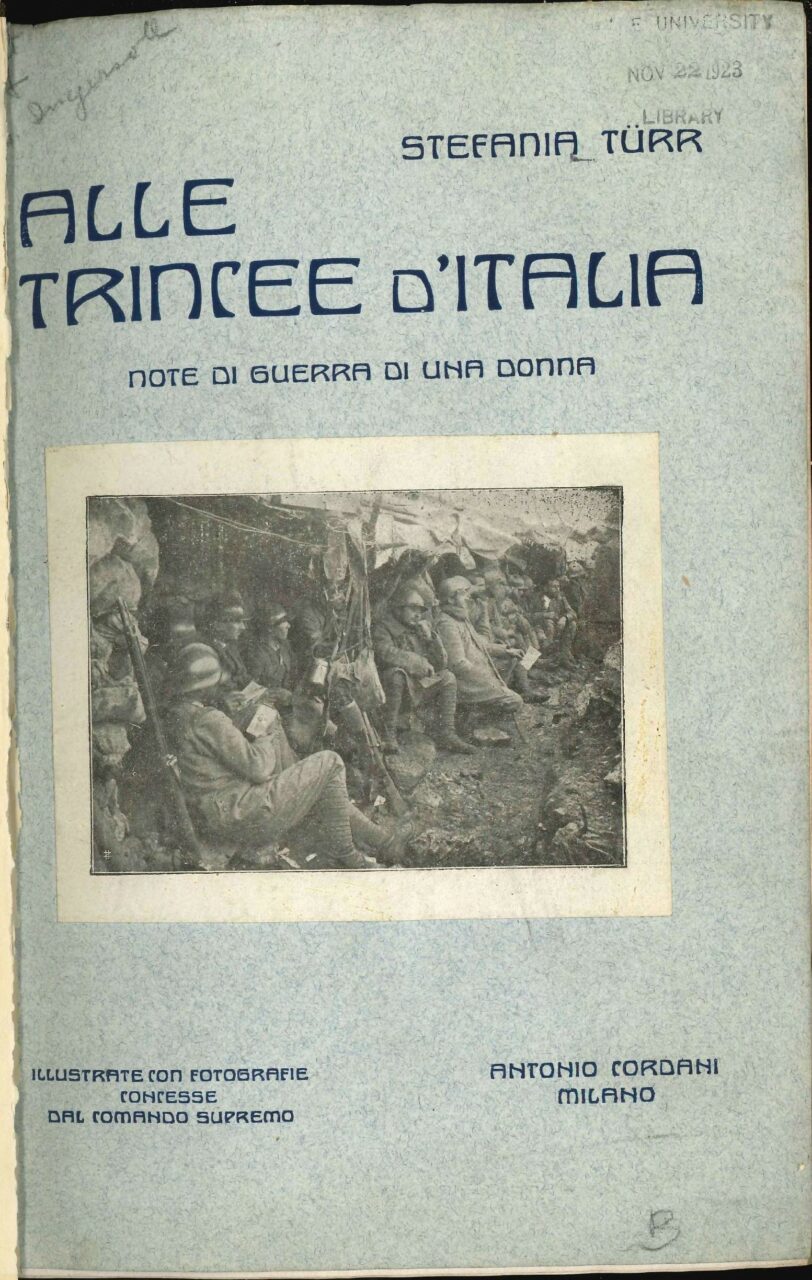

In 1917, Stefania Türr wrote Alle Trincee d’Italia. Note di guerra di una donna (At the Trenches of Italy: A Woman’s War Notes), a book-length account of her visit to the front, emphasizing the female perspective on the war. In 1918 she published a children’s version of her book, written with a pedagogical and propagandistic intent: I soldati d’Italia. Racconti della guerra (The Soldiers of Italy. Tales of the War). It explained the causes of the First World War and the development of the conflict with the aim of furthering patriotic education. Both books reprinted numerous photographs with permission from the Italian High Command.

Photo: Stephanie Seul

Türr was an enthusiastic and courageous journalist who threw herself headlong into the narration of the war. If it had been possible for a woman, Türr would have participated in combat. Instead, she was content with visiting the fighting lines, talking to the soldiers about their war experiences, and rousing the admiration of her readers for the brave Italian soldiers. In the preface to Alle trincee d’Italia she writes:

My aim in writing this book was to extol the virtue of our soldiers who had suffered so much and done so much for their country. (…)

It is necessary for the army to feel that the nation has faith in it; that the soldiers, in the sacrifice of their lives, feel that the people are in devout admiration. And you will draw firm confidence that the army is great, the soldiers valiant.

Italians! A single shout erupt from your breasts: Long live Italy! Long live the army!13Türr, Stefania: Alle trincee d’Italia: Note di guerra di una donna. Libro di propaganda illustrato con fotografie concesse dal Comando Supremo. Milano: A. Cordani, 1917, pp. 5, 8.

Little is known about Stefania Türr’s life after the First World War. Unlike Matilde Serao and Flavia Steno, she leaned towards Fascism in the interwar years. She continued her career as a writer and published several books, among them a travelogue and a biography of her father Stefano Türr. She died in Florence in 1940, aged 55.

Matilde Serao, Flavia Steno and Stefania Türr are pillars of Italian female journalism in the early Twentieth century. Although their words sometimes suffer from pompous rhetoric, due to a heartfelt patriotism and the fact that they were concerned mothers, they are worthy of being considered the mouthpiece for Italian women during the First World War. Importantly, they recognised how the devastating conflict brought to the surface the shortcomings of the position women in Italian society and showed how much change was needed.

War publications by Matilde Serao, Flavia Steno and Stefania Türr

Serao, Matilde: Parla una donna: Diario feminile di guerra, Maggio 1915 – Marzo 1916. Milan: Fratelli Treves, 1916.

Steno, Flavia: Milano: Guerra di popolo. Milano: Fratelli Treves, 1917.

Ariel (F. Steno) [Flavia Steno]: Il Germanesimo senza maschera. Milano, Fratelli Treves, 1917.

Deni, Mauro [Flavia Steno]: Per non dimenticare: Pagine per la guerra e per la pace. Milano: Fratelli Treves, 1919.

Türr, Stefania: Alle trincee d’Italia: Note di guerra di una donna. Libro di propaganda illustrato con fotografie concesse dal Comando Supremo. Milano: A. Cordani, 1917.

Türr, Stefania: I soldati d’Italia: Racconti della guerra. Libro di propaganda illustrato con fotografie concesse dal Comando Supremo. Firenze: Bemporad e Figlio, 1918.

Notes

- 1Zangrandi, Silvia: “Una donna che parla alle donne: La Prima guerra mondiale vista da Matilde Serao in ‘Parla una donna’.” In Cuadernos de Filología Italiana 22 (2015), pp. 195-214, here pp. 201-202.

- 2Rasy, Elisabetta: “’Parla una donna’: Il diario di guerra di Matilde Serao.” In Chroniques italiennes 39-40 (1994), pp. 243-254.

- 3Quoted in Nadia Verdile: “Matilde Serao, la femminista antifemminismo”, 20 July 2019, https://vitaminevaganti.com/2019/07/20/matilde-serao-la-femminista-antifemminismo/ (accessed 25 November 2021).

- 4Quoted in ibid.

- 5Zangrandi, Silvia: “Una donna che parla alle donne: La Prima guerra mondiale vista da Matilde Serao in ‘Parla una donna’.” In Cuadernos de Filología Italiana 22 (2015), pp. 195-214, here p. 211.

- 6Pisano, Laura (ed.): Donne del giornalismo italiano. Da Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel a Ilaria Alpi. Dizionario storico biobibliografico. Secoli XVIII-XX. Milano: Franco Angeli, 2004, p.139; Carla Gubert: “‘We are exiting the realm of life, for real, to enter the theatre of war’: Flavia Steno’s reports from the front.” In Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 21,2 (2016), pp. 252-270.

- 7Quoted in Picchiotti, Antonella: Flavia Steno: Una giornalista, una donna (1875-1946). Genoa: Frillieditori, 2010, pp. 168

- 8Stolfi, Valeria: “Amelia Osta Cottini detta Flavia Steno (Lugano 1877 – Genova 1946).” In: Enciclopedia delle donne, online: http://www.enciclopediadelledonne.it/biografie/amelia-osta-cottini/ (accessed 29 November 2021).

- 9Picchiotti, Antonella: Flavia Steno: Una giornalista, una donna (1875-1946). Genoa: Frillieditori, 2010, p. 175; Carla Gubert: “‘We are exiting the realm of life, for real, to enter the theatre of war’: Flavia Steno’s reports from the front.” In Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 21,2 (2016), pp. 252-270.

- 10Stolfi, Valeria: “Amelia Osta Cottini detta Flavia Steno (Lugano 1877 – Genova 1946).” In: Enciclopedia delle donne, online: http://www.enciclopediadelledonne.it/biografie/amelia-osta-cottini/ (accessed 29 November 2021).

- 11Picchiotti, Antonella: Flavia Steno: Una giornalista, una donna (1875-1946). Genoa: Frillieditori, 2010, p. 180.

- 12“Questioni femminili.” In La madre italiana, III, 10, 1918, p. 380, quoted in Frattolollo, Angela: I ruoli della donna nella Grande Guerra. Fano: Sonciniana, 2015, pp. 47-48.

- 13Türr, Stefania: Alle trincee d’Italia: Note di guerra di una donna. Libro di propaganda illustrato con fotografie concesse dal Comando Supremo. Milano: A. Cordani, 1917, pp. 5, 8.