During the Second World War, the BBC’s German-language broadcasts and British leaflets dropped by the Royal Air Force were an important alternative source of information for many Germans. Germany’s media had been strictly censored and manipulated since 1933. Listening to foreign radio stations was illegal and penalties ranged from fines and confiscation of radio sets to imprisonment in a concentration camp, or even capital punishment. But the ban did not prevent Germans from listening to the BBC and reading British leaflets by their millions.

CC0 1.0 Universell – Public Domain Dedication

Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek

The British government started its propaganda campaign in the crucial days before the Munich Conference on 27 September 1938, when war and peace hang in the balance. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain decided to address the German people personally over the radio and to appeal to them to help him save peace or prevent the outbreak of war. Thereafter, the BBC, at Whitehall’s request, regularly broadcast a German-language programme that included news and political commentary. Its aim was to inform the German public about British efforts to appease Hitler, to avert war and to encourage Hitler to seek a peaceful solution to his territorial claims.

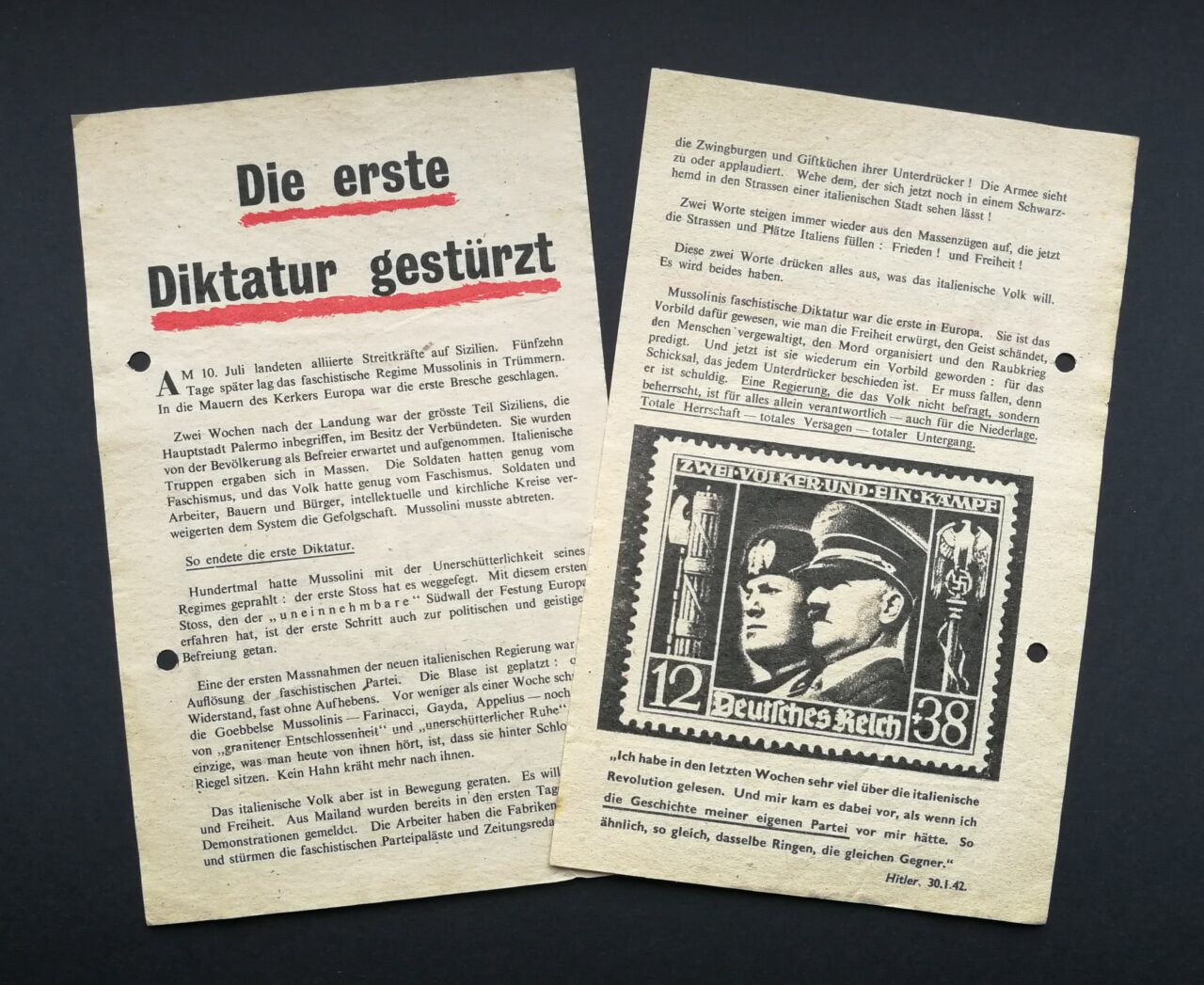

On the outbreak of the war on 3 September 1939, the British government greatly intensified its propaganda campaign. In addition to the German-language broadcasts, the Royal Air Force dropped millions of leaflets over the Reich. These measures were not only aimed at informing the German people about the British view of the war, but they sought to reduce the German fighting morale and stir up popular resistance against the Nazi regime. The British propaganda strategy during the ‘phoney war’ from September 1939 until May 1940 was based on the assumption that the regime in Germany was weak and that the population was hostile to Nazi rule. British propaganda called upon the German people to overthrow Hitler, to set up a more moderate government, and to conclude an honourable peace with the Allies. However, this strategy failed.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H12967 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

After the fall of France in June 1940, Britain was in a desperate strategic position. Despite having lost all its continental allies during the German Blitzkrieg campaigns, London decided to continue the struggle against Germany alone. It was doubtful whether Britain could win the war without help from abroad. In view of Hitler’s victories in Western Europe, no one in London seriously hoped for an immediate internal collapse of the German home front. The new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, left no one in doubt that he intended to defeat Germany on the battlefield rather than relying on propaganda. Even so, Churchill never contemplated discontinuing the propaganda campaign. In view of her military inferiority, Britain needed to make use of all available means – including propaganda and subversive warfare.

Ground crewmen hand propaganda leaflets to a crew member of Armstrong Whitworth Whitley Mark V, N1386 ‚DY-P‘, of No. 102 Squadron RAF at Driffield, Yorkshire, prior to a leaflet-dropping sortie over Germany.

Imperial War Museum, Public Domain

Publications originating from this project broadly focus on three topics

- The role of propaganda in Chamberlain’s appeasement policy and warfare towards Nazi Germany. I argue that contrary to conventional interpretations, appeasement was not a foreign policy pursued exclusively on a governmental level. Rather was it a policy that was at the same time addressed to the German public by way of propaganda. After Munich, propaganda played an increasingly important role in Chamberlain’s policy. Hardly a week passed without some important high-level governmental decision regarding the media campaign against Germany. During the ‘phoney war’ the War Cabinet had every single dropping of leaflets by the Royal Air Force over Germany reported to them. By integrating the media into his foreign policy, Chamberlain transformed British diplomacy from a purely inter-governmental strategy into a transnational policy in which the borders between domestic and foreign policy became blurred because this policy was aimed as much at the government as at the public of a foreign state.

- The British response to Hitler’s propaganda for a ‘New European Order’ during 1940-41. Following the defeat of France in June 1940, the Nazi regime announced ambitious plans for the economic and political reconstruction of Europe under German domination. Simultaneously, Great Britain was attacked as the backward defender of the old order. The Churchill government, concerned about the evident decline of its political influence in Europe, decided to take on the challenge and offer a rival, and better, plan for post-war Europe. Particular attention is being paid to the British propaganda campaign directed at the German public.

- The representation of the Nazi persecution and extermination of the Jews from the ‘Kristallnacht’ pogrom in 1938 until the collapse of the Third Reich in 1945. I analyse the factors that influenced accounts of the persecution of the Jews. Although British propaganda reported regularly on the Nazi treatment of the Jews, in retrospect it is clear that the reporting was too infrequent and failed to do justice to the scope of the Holocaust. This failure can in part be explained by the objectives of British propaganda: the BBC broadcasts and leaflets were not so much intended to inform the German public about the Nazi crimes against the Jews, but to help the Allies achieve victory. Other factors limiting the coverage of the Holocaust were the fear of playing into the hands of Nazi propaganda; certain British assumptions about the German mentality, in particular the spread of antisemitic attitudes; and, last but not least, latent antisemitic tendencies in the BBC and British government circles.

Together with Nelson Ribeiro I edited a special issue of the journal Media History (2015) on the BBC’s foreign-language services during the Second World War.

Research for this project was funded through Ph.D. scholarships by the German Historical Institute London, the German Academic Exchange Service DAAD, and the European University Institute Florence.

Publications

Seul, Stephanie: “’For a German Audience We Do Not Use Appeals for Sympathy on Behalf of Jews as a Propaganda Line’: The BBC German Service and the Holocaust,” in Simon Eliot and Marc Wiggam (eds.), Allied Communication to the Public during the Second World War: National and Transnational Networks. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, pp. 131-48.

Seul, Stephanie: “The Absence of ‘Kristallnacht’ and Its Aftermath in BBC German-language Broadcasts during 1938–1939,” in Wolf Gruner and Steven J. Ross (eds.), New Perspectives on Kristallnacht: After 80 Years, the Nazi Pogrom in Global Comparison (The Jewish Role in American Life: An Annual Review, vol. 17). West Lafayette, Indiana: Perdue University Press, 2019, pp. 171-93.

Seul, Stephanie: “Diplomatie und Propaganda als komplementäre Säulen in Chamberlains Appeasement-Politik” [Diplomacy and Propaganda as Complementary Pillars of Chamberlin’s Appeasement Policy], in Peter Hoeres and Anuschka Tischer (eds.), Medien der Außenbeziehungen von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau, 2017, pp. 315-36.

Ribeiro, Nelson, and Stephanie Seul (eds.): “Revisiting transnational broadcasting: The BBC’s foreign-language services during the Second World War.” Media History 21,4 (2015).

Seul, Stephanie, and Nelson Ribeiro: “Revisiting transnational broadcasting: The BBC’s foreign-language services during the Second World War,” Media History 21,4 (2015), pp. 365-77. Co-authored with Nelson Ribeiro.

Seul, Stephanie: “’Plain, unvarnished news’? The BBC German Service and Chamberlain’s propaganda campaign directed at Nazi Germany, 1938-1940,” Media History 21,4 (2015), pp. 378-96.

Seul, Stephanie: “Journalists in the Service of British Foreign Policy: The BBC German Service and Chamberlain’s Appeasement Policy, 1938-1939,” in Frank Bösch and Dominik Geppert (eds.), Journalists as Political Actors. Transfers and Interactions between Britain and Germany since the late 19th Century. Augsburg: Wißner-Verlag, 2008, pp. 88-109.

Seul, Stephanie: “The Representation of the Holocaust in the British Propaganda Campaign Directed at the German Public, 1938-1945,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 52 (2007), pp. 267-306.

Seul, Stephanie: “’Any reference to Jews on the wireless might prove a double-edged weapon’: Jewish images in the British propaganda campaign towards the German public, 1938-1939,” in Martin Liepach, Gabriele Melischek and Josef Seethaler (eds.), Jewish Images in the Media (Relation, n.s. vol. 2). Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2007, pp. 203-232.

Seul, Stephanie: “Europa im Wettstreit der Propagandisten: Entwürfe für ein besseres Nachkriegseuropa in der britischen Deutschlandpropaganda als Antwort auf Hitlers ‘Neuordnung Europas‘, 1940-1941“ [Rival Blueprints for Post-War Europe: British Efforts to Counter National Socialist Propaganda on the „New European Order“, 1940-1941], Jahrbuch für Kommunikationsgeschichte 8 (2006), pp. 108-161; PDF

Seul, Stephanie: “Appeasement und Propaganda 1938-1940. Chamberlains Außenpolitik zwischen NS-Regierung und deutschem Volk” [Appeasement and Propaganda, 1938-1940: Chamberlain’s Foreign Policy in Relation to the National Socialist Government and the German People]. Ph.D. dissertation, European University Institute Florence, 2005. Open Access Publication: Cadmus EUI Research Repository, DOI: 10.2870/94615.

Seul, Stephanie: “British radio propaganda against Nazi Germany during the Second World.” M.Phil. dissertation, University of Cambridge, UK, 1995. Open Access Publication: Apollo – University of Cambridge Repository, DOI: 10.17863/CAM.14329.